Inspiration

A Little Less Conversation, A Little More [Re]Action, Please

By lesly kahn | August 31, 2016In “The 25 Best Gunfighters in TV and Movie History,” on complex.com, Brenden Gallagher writes the following about Clint Eastwood as The Man With No Name in THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE UGLY:

Though sometimes he goes by “Joe,” other times by “Manco,” and still at other times by “Blondie,” we ultimately know him as the Man with No Name, and he is perhaps the most iconic figure of the western genre. The climactic duel of The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly alone has been the subject of homage and parody countless times.

[Clint] Eastwood’s performance is a reminder to our dialogue-heavy generation that, sometimes, less is more. Eastwood famously insisted some of his lines be cut from A Fistful of Dollars. From then on, the Man with No Name’s stoicism only increased and his popularity among moviegoers only grew. When Eastwood does speak in the trilogy, it counts . . . .

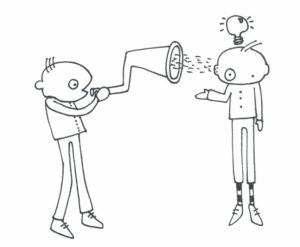

This article got me thinking about the relationship between actors, dialogue, and what Lesly refers to as the white space. Typically, actors want MORE lines, not less, but that can prove to be a mistaken viewpoint. The actors who GET it are the ones who understand that, in TV and film, it is not what is said or done that has the greatest impact on an audience; it is the thoughts that the actors are thinking about what was just said or done that create a brilliant performance. Eastwood seems to have instinctively known this, and his portrayal of The Man with No Name became such an iconic performance largely due to the fact that, by cutting his own lines, Eastwood ensured that his screen time would largely consist of shots of his character reacting to events and what the other characters said or did. And reacting is, essentially, having a thought about what was just said or done. Audiences loved the character of The Man with No Name because, I would argue, they got to see what Lesly would describe as a real, live, incredibly interesting, and specific person in a real, live, incredibly interesting, and specific situation.

Another film great, Michael Caine, has also touched on this topic. In his book Acting in Film, Caine writes about his surprise when, as he started working in Hollywood, he came across actors who wanted to cut their own lines out of their scripts:

Movie actors earn their living and learn their craft through listening and reacting. I noticed that American actors always try to cut down their dialogue. They say, “I’m not going to say all of this. You say that line. At first I couldn’t figure out why; I came from theatre, where you covetously count your lines. But it’s a smart approach for an actor to give up lines in movies because while you wind up talking about them, they wind up listening and reacting. It’s no accident that Rambo hardly speaks. Sylvester Stallone is not a fool . . . . I can’t say it enough: one of the most important things an actor can do in a motion picture is to listen and react as freshly as if it were for the first time.

Coming from a theatre background, Caine had fallen into the trap of counting lines (for a hilarious take on this subject, along with other problems with our “classical” training system, listen here). Fortunately for him, and for moviegoers everywhere, he quickly came to realize that, in film and TV, it is the visual reactions and the ability to see the character’s thoughts through their eyes that carry the greatest weight. I love Caine’s description of listening and reacting “as freshly as if it were for the first time.” That is, after all, what all actors strive to achieve. But how do you do that? You do it by having character thoughts about whatever was just said or done. That is what “actively listening,” as Caine described it, is.